Storytelling teahouse ‘master’ is modern day doctor of the soul

First published by The Japan Times

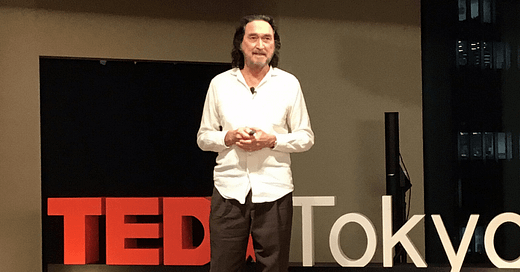

The work we do in life is often connected with who we are as people. So it was for Dr. Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu, a Japanese-American. He made mixed-race identity the focus of doctoral studies at Harvard University and the basis of a career teaching psychology at prestigious institutions, including University of Tokyo and Stanford.

When he first started researching mixed-race studies, he thought being a ‘hafu’ separated him from others. Now, aged 68, he feels it connects him.

Born whole, people gradually suffer early life experiences. Parents and others tell us who we are and who we are not, what we can and can’t become because we are female, black, ‘hafu’ or whatever, he says. Stories like these can lead to feelings of isolation and alienation. But stories are also medicine: “A story told one way can harm. A story told another way can heal,” he explains.

Today, Murphy-Shigematsu combines Eastern and Western ideas of storytelling, mindfulness and compassion in ways which help groups of students reframe their past painful narratives into more positive and helpful ones. The self-proclaimed modern doctor of the soul practices his trade in metaphorical Zen tearooms.

Born in Tokyo in 1952 to an Irish-American father and Japanese mother, Murphy-Shigematsu grew up in Massachusetts after the family moved stateside in 1953. As a child, he learned to love American hotdogs, Dunkin Donuts and McDonald’s hamburgers.

Everyone in his small town was Caucasian. Many never met an Asian before. Most didn’t know the difference between a Japanese and Chinese person. Some townsmen, still traumatized by World War II, were outwardly hostile to people they called ‘Japs’. It didn’t happen often, but it still bothered him. “As children, we could feel the hostility some people had,” he recalls.

More unsettling, he felt others didn’t see him as being American. Previous generations of European immigrants encountered similar discrimination in varying degrees. Over time they assimilated. “They were considered American, but I wasn’t,” laments Murphy-Shigematsu. As time passed, he felt a growing sense of isolation.

Later, he won a scholarship to attend an East Coast private boarding school which had a growing diverse student body. His roommate, Purcell Brown, introduced him into the African American community. Murphy-Shigematsu’s new friends couldn’t relate to his Japanese ethnicity, but they knew he wasn’t white. So they made him an honorary black. It was a “transformative experience,” he recalls, to feel social acceptance for the first time.

The school even joked about his transformation at the graduation ceremony. In a segment meant to rouse memories of shared moments they announced, “Bill Taylor leaves his hockey stick; Steve Murphy (Shigematsu) leaves almost black.” The story may not be word-for-word precise, but it stuck in his mind. Of course he knew he wasn’t black. Nor was he Chinese. And he certainly wasn’t white. “I figured I must be Japanese,” he says.

Murphy-Shigematsu built his studies and professional career around trying to integrate different identities while finding his place in the world. He trained seven years at Harvard to become a clinical psychologist. After graduation, he conducted fieldwork in Okinawa as a Fulbright scholar. There he listened to the stories of socially marginalized Okinawans.

After the war, local women from Okinawa gave birth to mixed-race children fathered by US military personnel. Many fathers then abandoned their families, leaving mothers to single parent. These women often took jobs at local bars to survive, leaving their children unattended. As students, many children were bullied, causing them to drop out of school, leading to a repeating pattern of drug addiction, prostitution, crime and poverty. There were, of course, also stories of resilience and success.

Murphy-Shigematsu heard them all, becoming a good listener. He learned to listen with his heart, an art called ‘deep listening’. It was, he says, “a gift to be able to receive a story.” It was also a gift to offer ‘deep listening’ to people with whom he shared so much in common.

In the early 1990s, he left Okinawa to teach at Temple University, Japan Campus. TUJ students also came to him for counseling. “I got to know many students intimately that way, sharing their struggles,” he recounts. Later he became a tenured professor at University of Tokyo, where he continued to counsel and to teach students on subjects of Japanese culture, mind and society.

He worked hard over many years to integrate into society, even naturalizing as a Japanese citizen and adopting the surname Shigematsu. As he built his reputation, publishers, institutions, associations and others asked him to give talks, write books and join their boards. Colleagues accepted him into their tribe: “I was officially and informally treated as Japanese at work,” he contends. Still, he remained conflicted. After all, he was also an American.

Though he was on track towards a successful career in Japan, he gave it all up in 2002 to become a professor at Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, California. Since, he has authored many books, including “From Mindfulness to Heartfulness: Transforming Self and Society with Compassion” and "When Half Is Whole: Multiethnic Asian American Identities". He also started a group community healing ritual he calls the Storytelling Teahouse (see below).

After 17 years living in America, Murphy-Shigematsu says he feels more connected to the land and people of Japan. The frequent Tokyo visitor plans in a year or two to make Japan his permanent home. His life’s journey will then have returned full-circle to his country of birth.

The Storytelling Teahouse (Japan Times link)

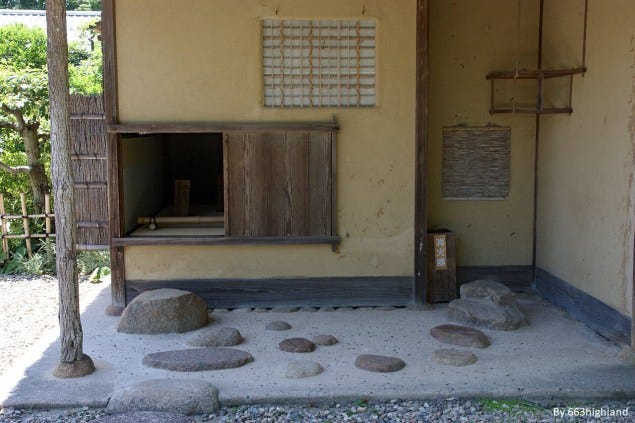

The storytelling teahouse is any safe place where students can express themselves by sharing their private thoughts. In the metaphorical storytelling teahouse it’s possible to tell things to perfect strangers that one might never tell one’s closest friends because they treat each other with respect, he says. It is a place where, “I tell you my story. You listen to my story. You tell me your story. I listen to your story.”

He developed the idea from teahouses constructed during the Kamakura period (1185 and 1333) like the one pictured above. The teahouses, built by Zen monks, are simple and tranquil places to practice the tea ceremony. Samurai removed their swords to get through a purposely-made small and low entrance. Stripped of sword and title everyone is equal in the tearoom. Likewise, anyone entering his storytelling teahouse must “place ego in one pocket and humility in the other.”

Students also enter with a ‘beginners mind’ which simply means focusing on the present moment to experience being fully alive ‘now’. They achieve ‘beginners mind’ by practicing meditation at Stanford’s meditation center. Or they take Zen walks—slow and deliberate meditative walks around a quiet lake.

Many people practice meditation to achieve peak performance. Murphy-Shigematsu believes this type of mindfulness is useful but too inward focused. He preaches another more outward-looking form which connects people to one another he calls heartfulness. With its practice, students feel a heartfelt sense of connectedness which is community building, he says.

Perhaps the Japanese proverb ‘ichi-go ichi-e’ (meaning one time, one meeting) captures the essence of the storytelling teahouse. Each moment in the teahouse approached with humility, equality, gratitude, acceptance and vulnerability is a chance to connect with others in ways that will never repeat. He reports that students find the experience life-changing.

Murphy-Shigematsu is the storytelling teahouse master or ‘sensei’. This does not mean he is above his students. Rather it means, as their elder, he is ahead of them down the path of life. They can accept his mentoring, if they choose. But he is also there to learn. He leads by sharing a story of his own. “As I show my own humanity, students start showing theirs,” he says. From there, “It just ripples.”

A family story with bicultural roots (Japan Times Link)

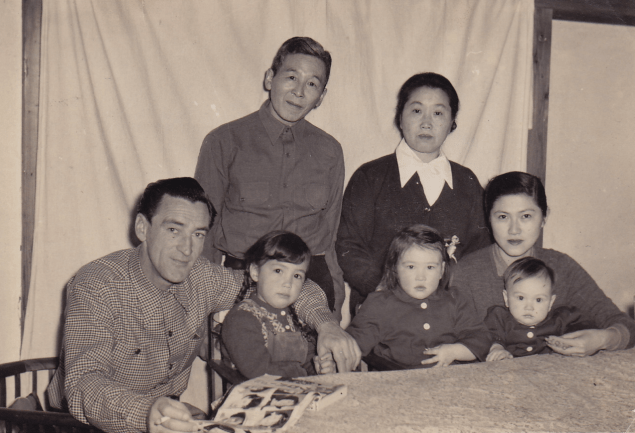

Murphy-Shigematsu has two families, one hailing from Ireland and the other from Japan. His paternal ancestors emigrated from Southwest Ireland to the Northeastern US toward the end of the 19th century. His grandmother died when his dad was a child, leaving her the eldest of six siblings to raise the family.

On his mother’s side, his great-grandfather was a hatamoto, a samurai in direct service to the shogun. His great-grandfather changed his name from Yamamoto to Shigematsu, after fleeing the 1868 battle of Ueno during the Boshin War. He fled to the town of Matsuyama where he was protected by friendly samurai.

Murphy-Shigematsu’s parents met after World War II. Both worked in the GHQ building (she as a translator) which served as SCAP General Headquarters.

His two older sisters were born out of wedlock. Mixed marriages were not allowed in Japan then. It was also difficult to get proper paperwork to take his mother to America. But his grandmother said that his father could move into her house (where his mother also lived) because he was clearly a man who respected his mother and Japanese people. “She was far ahead of her time,” Murphy-Shigematsu suggests.

His dad moved in and his two sisters were born Shigematsu in 1949 and 1950. They gained Japanese citizenship under Nationality Law which allows children of unmarried couples born here to do so. Murphy-Shigematsu was born Murphy in 1952, an American citizen, after Japan marriage laws changed to permit mixed-race marriages.

Later his dad became lonely living as a foreigner in Japan. He wanted to show his wife and children to his American family. In 1953, the entire family left Yokohama by boat to settle in Massachusetts. The journey meant saying farewell to Murphy-Shigematsu’s maternal grandparents, which devastated his grandmother.

She had none of her own children, but had adopted her younger sister who was 20 years her junior. In those days, such adoption was not uncommon. Murphy-Shigematsu and his two sisters were born in his grandmother’s house. When the family left for Massachusetts, his grandmother had to part with all three babies she helped rear. He did not see his grandmother again for two decades. “This was a period when once you left, often you never came back,” which greatly grieved his grandmother, he says.

Murphy-Shigematsu reconnected with her when he was in his early 20s. She was already 76-years old. He lived with her in Matsuyama, where she taught him Japanese language and culture. “As a troubled adolescent, she gave me new life just to be with her,” he says. Their special relationship continued until her death, aged 111.

Beacon Reports reveals Japan through the lens of thought leaders.